Fashion lacks urgency when it comes to the climate emergency, according to newly revealed data on 2,500 brands’ environmental track records.

Key stats based on Good On You’s brand ratings—published here for the first time:

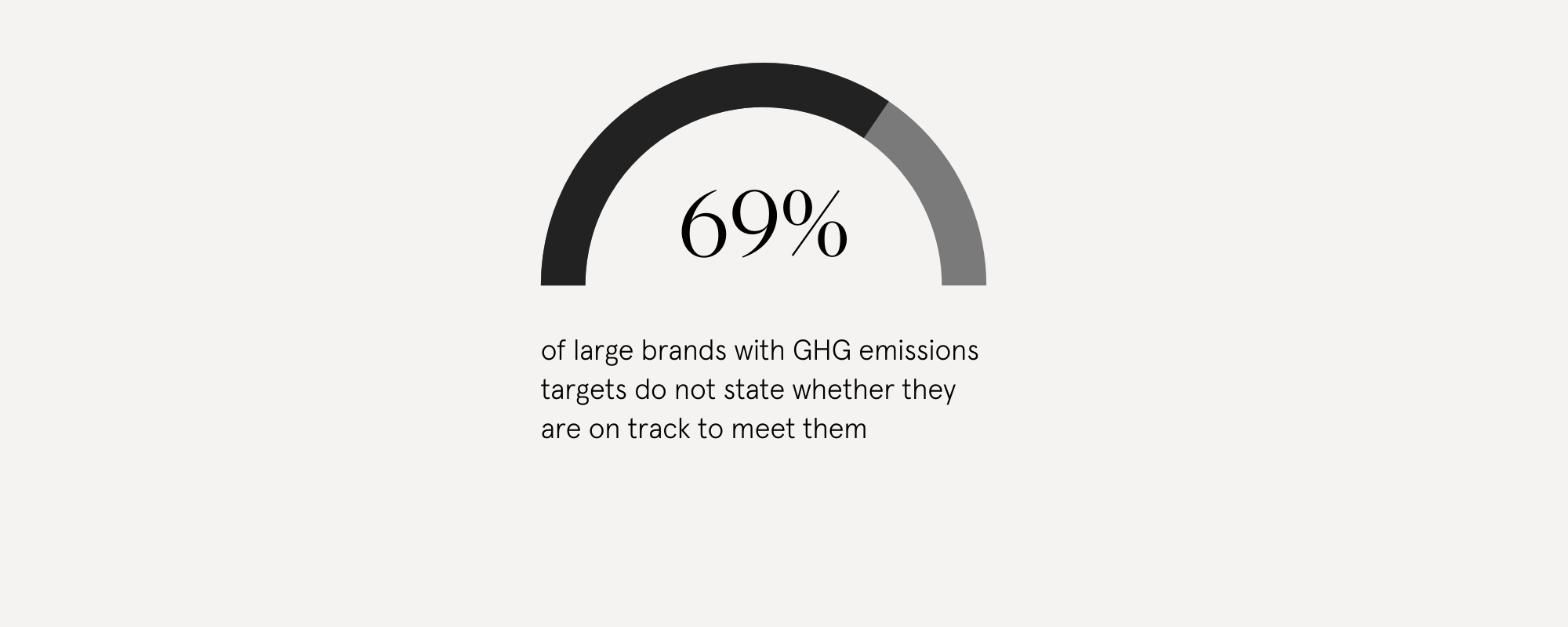

- 69% of large brands with greenhouse gas emissions targets do not state whether they are on track to meet them. This reflects the industry’s lack of transparency. It also underscores the need for governments to mandate companies reporting on greenhouse gas emissions.

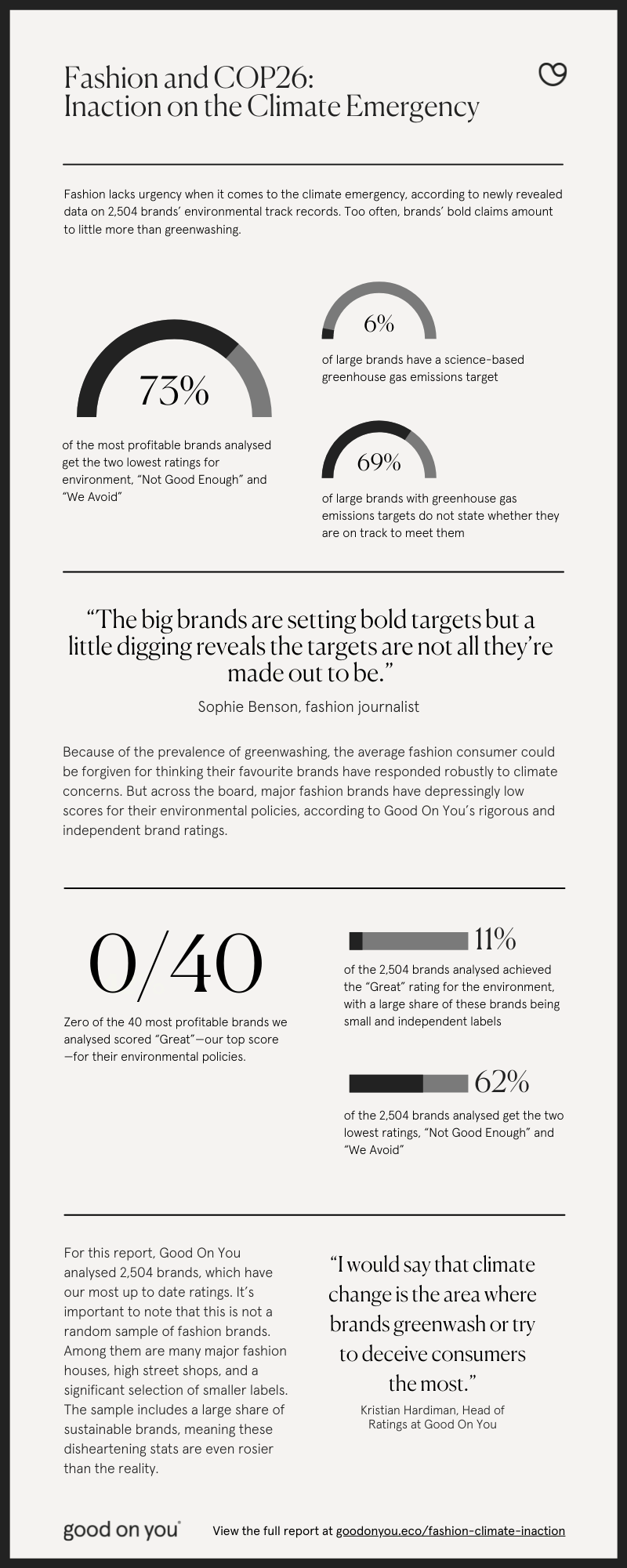

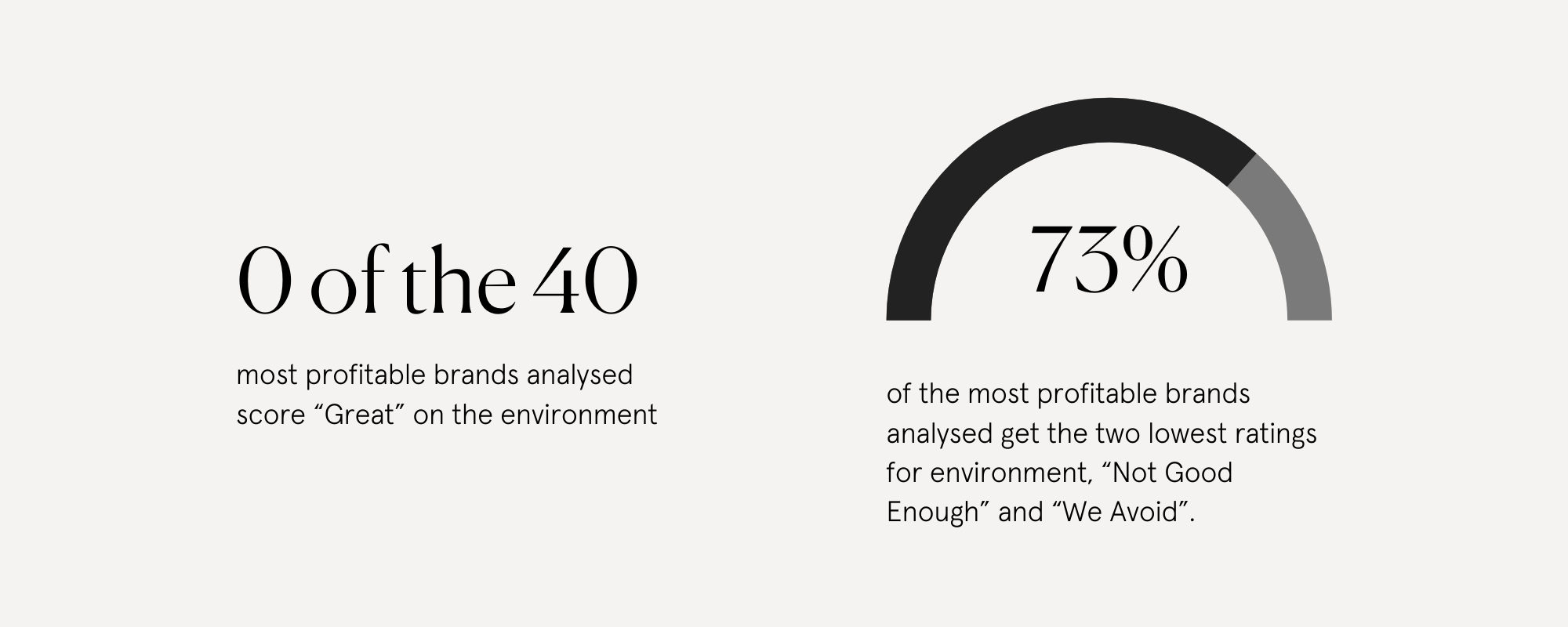

- 0 of the 40 most profitable brands analysed receive Good On You’s top rating—“Great”—for the environment. This means these brands are not demonstrating leadership in environmental policies, transparency, or managing material issues across their supply chains.

- 73% of the most profitable brands analysed get the two lowest ratings for environment, “Not Good Enough” and “We Avoid”—meaning these brands publish little or no concrete information about their sustainability practices and are not adequately managing their impacts across their supply chains. In some cases, these brands may make ambiguous claims that are unlikely to have a material impact.

- 26% of brands scored “Good” or “Great” across all areas (environment, labour, and animal welfare), demonstrating how the industry can do much better. This includes a large share of small and independent labels along with a few major brands showing leadership.

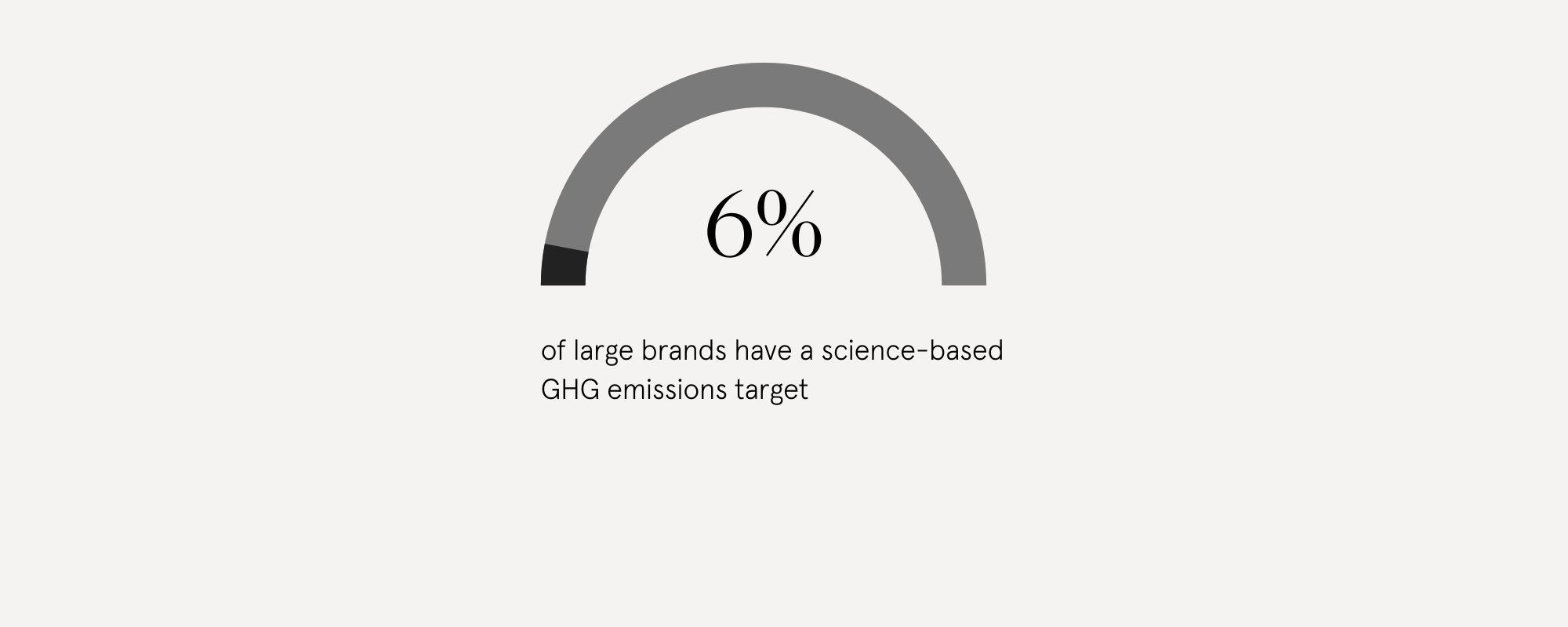

- Only 6% of large brands have a science-based greenhouse gas emissions target. Read on to see why this matters.

New data shows fashion’s climate inaction

The climate emergency is “code red” for humanity, according to a major UN report. But everywhere you look, from political slogans to fashion campaigns, we often hear greenwashing more than we see meaningful action.

As COP26 gets underway in Glasgow—that is, the 26th meeting of the 197 signatories of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change—we’ve hit a critical moment for the future. And the focus is rightly on how our leaders have failed to act.

The COP26 context

As part of the 2015 Paris Agreement, which saw nations pledge to make efforts to limit global warming to “well below” 2 degrees and ideally 1.5 degrees, governments were asked to create action plans. But it was up to them to decide what action to take, and they missed the mark significantly. An interim report released in February 2021 revealed that “governments are nowhere close to the level of ambition needed to limit climate change to 1.5 degrees and meet the goals of the Paris Agreement,” according to UN Secretary-General António Guterres.

Now, in line with the Paris Agreement’s “ratchet mechanism”, which ensures climate action becomes more ambitious over time, governments are expected to submit new action plans at the conference, progressing on previous plans. With COP26 president Alok Sharma telling world leaders to “step up”, the world is holding its breath.

Fashion’s lack of urgency

Reporting around COP26 centres, unsurprisingly, around government action, or a lack thereof. However, the scorecard for businesses, which the UN calls “non-state actors”, is equally poor. As an industry that spans the globe, with single garments often traversing between countless countries including China, the US, the UK, Vietnam, India, Ghana, and Bangladesh within their lifecycle, fashion has a major stake in the future of our climate. But fashion seriously lacks a sense of urgency.

Reliable, peer-reviewed figures are hard to come by—in part because of the fashion supply chain’s inherent complexity. But the UN estimates that the multi-trillion-dollar industry is responsible for 8-10% of the world’s greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. As an industry predicated on growth, that figure could well increase if left unchecked. And in a world scrambling to limit emissions, that’s a dangerous prospect.

Good On You data sheds light

It’s important that we have a handle on what impact the fashion industry is having and where it’s going.

Given that there’s no COP for fashion brands—no mandated progress disclosure—it’s difficult to track. That’s where Good On You’s comprehensive data on fashion brands comes into play. Having rated thousands of brands over the past six years, this data can give us a sense of the industry’s report card on environmental policies. Spoiler alert: It’s too much greenwashing, too little action.

Greenwashing is rampant

The average fashion consumer could be forgiven for thinking their favourite brands have responded robustly to climate concerns. From environmental mission statements to promises of cutting emissions and eliminating waste, the fashion industry outwardly seems to have transformed into a custodian of our collective future. “Fashion made from waste and grapes? Welcome to the future”, says one high street behemoth. “We’re facing up the future, doing more for our clothes, our suppliers, our communities, and our impact on the environment,” promises another brand.

It appears that every fashion brand is doing its very best, setting targets such as “we’ll achieve net zero across our value chain by 2030”, and “[our goal is to] be climate positive by 2040”. However, beyond the snappy promises lies a very different reality.

That’s what’s often considered greenwashing—the unjustified and misleading claims from fashion brands that their products are more environmentally friendly than they really are. This manifests in various ways. Sometimes it’s outright deception. Sometimes it’s more subtle advertising. Often, it’s brands making ambitious claims without being transparent around their actual impacts.

Beyond avoiding those misleading claims, the most effective response to greenwashing is for brands to be fully transparent about their impact and how they’re addressing the key issues in their supply chains. That’s why this report goes beyond the greenwashed claims and focuses on data about what brands are really doing.

Most brands are not doing enough

Most fashion brands get low scores for their environmental policies, according to Good On You’s rigorous and independent brand ratings. To rate brands, Good On You looks past each brand’s claims and analyses its actions across more than 100 key sustainability issues. Good On You considers a variety of indicators of environmental impact and progress. These include emissions reduction activities, target setting, and the measurement of scope one, two, and three GHG emissions (this means not only counting emissions from brand-controlled sources like offices and warehouses but all indirect emissions like those from energy use, purchased products, and even employee commuting). The environmental ratings also factor in resource management, chemical use, and water use.

Each brand is labeled on a scale of 1 (“We Avoid”) to 5 (“Great”), with brands on the upper end of that scale representing the leaders for their policies. You can find out more about how Good On You’s ratings work here.

For this report, Good On You analysed 2,504 brands, which have our most up to date ratings. It’s important to note that this is not a random sample of fashion brands. Among them are many major fashion houses, high street shops, and a significant selection of smaller sustainable labels. The sample includes a disproportionate share of sustainable brands, meaning these stats are even rosier than the reality (percentages rounded to the nearest integer):

Small labels lead the way

Smaller sustainable brands are leading the charge for progress compared with large brands, which Good On You defines based on annual turnover. Their efforts boost the results and make Good On You’s industry-wide data look more impressive than it really is.

If we remove the more sustainable brands from the mix, you’re looking at a much bleaker picture. In other words, the sustainable brands in this sample demonstrate it’s possible to do much better.

Setting science-based targets

The big brands are setting bold targets, but a little digging reveals the targets are not all they’re made out to be. As we’ve seen, brands are rushing to set impressive-sounding targets to show their customers how concerned they are about the climate.

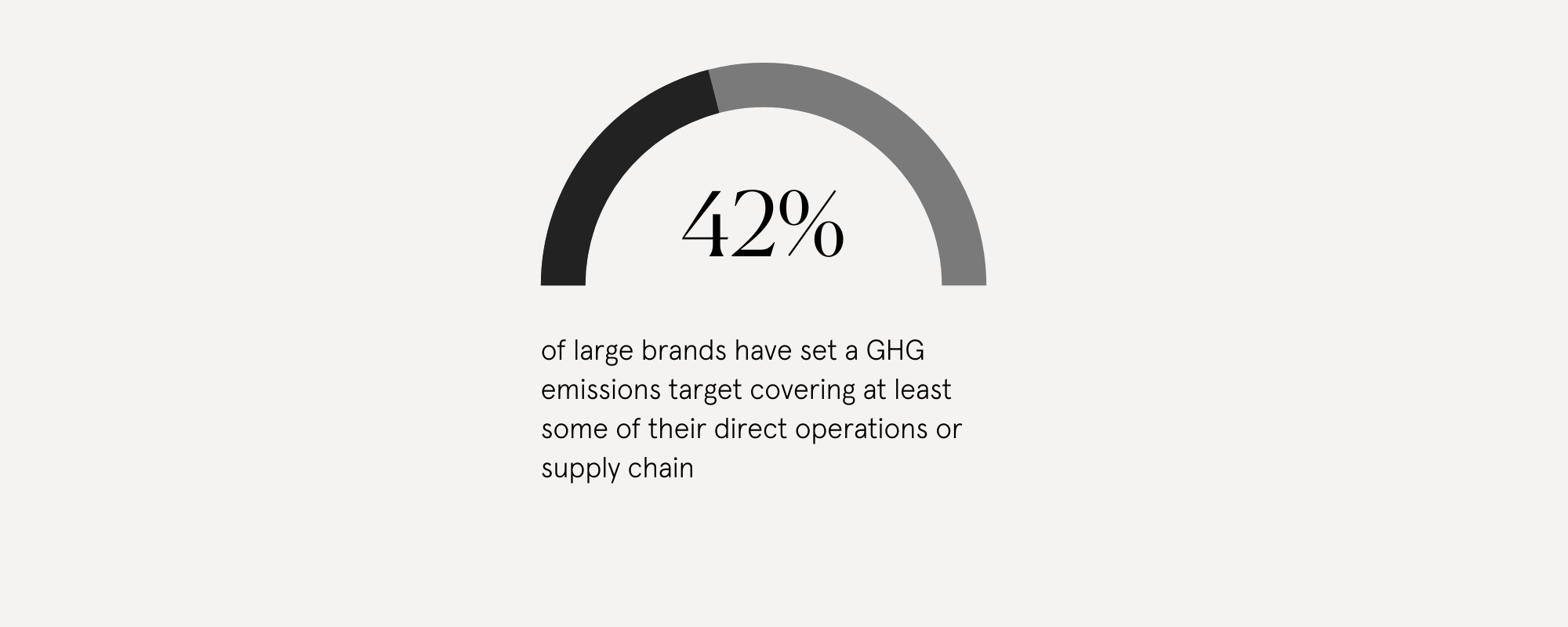

Nearly half. It sounds great, but some targets mean more than others.

It’s that “science-based” bit that really matters. Kristian Hardiman, Head of Ratings at Good On You, explains that the “base year” brands choose can make a huge difference. “When I first started working in climate change, loads of brands were setting 2007—the year before the global financial crisis—as their base year. Emissions were quite high and then they dropped, so if they set a target of a 30% reduction compared to 2007, they were already there, they didn’t really have to do much,” he says, adding that he expects 2019, the year before COVID, to become the next base year.

Science-based targets help to avoid that kind of sneaky carbon accounting by ensuring that targets are set in line with the internationally agreed 2 or 1.5 degree warming limit. “The Science Based Target initiative has really done the work of what it would mean for a company to align themselves with the Paris Agreement framework,” explains Maxine Bédat, author of Unraveled and Director of the New Standard Institute. “It’s a way to draw a line in the sand between corporate greenwashing and real action.”

Big money, little action

The most profitable fashion brands are getting the lowest scores for their environmental policies. Some pin hopes for the future on the largest companies with the thickest wallets to fund and drive solutions. But Good On You’s data suggests they’re simply not putting in the work.

For this report, Good On You looked at the ratings for the most profitable brands listed on FashionUnited’s annual index, considered by many to be the benchmarks of profitability across private and public brands. Of the top 40 brands analysed, the numbers paint a picture of the most powerful brands doing the very least.

“I would say that climate change is the area where brands greenwash or try to deceive consumers the most,” says Hardiman. That can be successful because consumers aren’t supply chain or carbon emissions experts.

“We can’t just rely on consumers because consumers can’t be deeply educated in all of these things. That’s way too much of an expectation to put on regular people,” says Bédat. “And so, what we’re seeing is tightening legislation.”

Fashion labels’ misleading claims

Greenwashing is a growing concern for consumer protections. Governments are taking some actions in this area—laws, guides to greenwashing, and prosecutions. But they are doing nothing to ensure brands measure and disclose their emissions.

One recent example of regulatory intervention is adidas, which found itself in trouble this past August when the Advertising Ethics Jury of the French advertising regulator, ARPP, deemed that an advert for its Stan Smith sneakers could mislead consumers. The sneaker, which is styled crushing a plastic bottle, was advertised as being “100% iconic, 50% plastic”. “The consumer is thus inclined to think that 50% of the Adidas sneakers represented are made of recycled materials,” reads the ruling, when in fact only the upper part of the trainer contained recycled materials. The Jury also took issue with the use of the “End Plastic Waste” logo, because “although the plastic used to make the promoted sneakers comes from the recovery of abandoned plastic waste … this does not mean recyclable plastic.”

Other brands including Allbirds and H&M have been up against accusations of greenwashing and misleading consumers. In the UK, the Competition and Markets Authority has launched the “Green Claims Code” in response to widespread official concern about misleading green claims. The code outlines which claims will be deemed “genuinely green”, giving brands just 3 months to tidy up their marketing to comply with consumer protection laws. Promises of “X% reduction by X year” will no longer cut it. Brands will be expected to explain which base year, which scope, and by which means they will reach said target.

Of course, ostensibly earth-friendly claims will draw consumers, and there are cynical forces at play, but fashion academic and strategist Frederica Brooksworth says a lack of education is also to blame where the professionals communicating these messages are concerned. Marketers are entering a seemingly creative profession and then tasked with relaying highly complex, scientific information in an accessible way. “I’ve been pushing for law to be taught on fashion programmes and I’ve run my own courses for three years,” she says. “We have a responsibility as educators to really enforce this within the curriculum. If you’re teaching fashion marketing, you need to look at it in terms of consumer protection.

Confessionals—the next marketing trend?

An emerging response to consumer and legal allegations of greenwashing is brands turning on their heels and being brutally honest about their shortcomings. Ganni decided to tell the world “Why we’re not a sustainable brand”, perhaps borrowing from Noah’s 2018 missive along the same lines, while Ace & Tate said, “Look, we f*cked up”, and listed five “bad moves” it had made as a brand, including setting an unrealistic carbon goal.

Certainly, these brands aren’t pretending to be greener than they are, but they are carving a path of least resistance, digging out leeway to do less, aim a little lower. “It’s fine, work on it, but just don’t make it your main message, because then it’s not authentic,” says Brooksworth.

Large brands not transparent about progress

On a consumer level, greenwashing erodes trust. On an environmental level, this lack of meaningful action further derails the path toward achieving the 1.5 degree limit. As the official “COP26 Explained” document reads, “If we continue as we are, temperatures will carry on rising, bringing even more catastrophic flooding, bush fires, extreme weather, and destruction of species.”

Nations are expected to revise and report on their action plans every five years and yet:

We’re at a critical tipping point for our future, and the pervasiveness of greenwashing means we simply do not know whether brands are acting on their own self-promoted plans. Updates and ambition are a key metric for COP26 and indeed a habitable climate in future, yet fashion brands who play a key role in protecting that future are obfuscating reality. Some major brands are being more transparent than they were a few years ago. We need to accelerate this change.

Today, many are calling for mandates and incentives for transparency from brands. This October, the UK’s Ethical Consumer released their Climate Gap Report, which recommended that governments make it mandatory for companies to report on their supply chain emissions—something that the vast majority of companies do not currently do (see stat below). There is precedence for such regulation. In the UK, the Modern Slavery Act of 2015 requires companies with turnover of more than £36 million to report on the steps taken to eliminate slavery in the supply chain. Australia and California have similar laws. Increasingly, activists want to see governments take similar steps with transparency around emissions in the supply chain.

With the window of opportunity closing, transparency seems like the bare minimum. “Saying that you can’t operate unless you are operating within the bounds of the planet,” Bédat says, “it seems eminently reasonable, doesn’t it?”