Fast fashion. A term used so often in the past two years, one might begin to think of it as a buzzword, instead of the business model it truly is. To define it, fast fashion is “cheap, trendy clothing that samples ideas from the catwalk or celebrity culture and turns them into garments in high street stores at breakneck speed to meet consumer demand.” Its model is based on trends and their popularity among consumers. In order to meet consumer demands, fast fashion brands must have the resources to not only manufacture these popular designs quickly, but also dispose of them with equal speed to make room for incoming trends. That’s why brands like ZARA and Forever 21 are so popular—they’re selling you the latest styles right when you want them, and taking them off the racks by the time you don’t. Seems harmless enough, this people-pleasing model. But a look at fast fashion’s environmental impact tells a different story.

A fast-paced model requires fast-paced production, and unfortunately, quicker production gives way to an increase in environmental damage.

A fast-paced model requires fast-paced production, and unfortunately, quicker production gives way to an increase in environmental damage. By doing such things as using toxic, water-wasting materials to produce textiles, and neglecting safe workplace protocols as a means of acquiring cheap labour, the fast fashion industry has become a detriment to our environment, having a carbon footprint that rivals all other industrial productions. Here’s a collection of statistics and explanations that portray the reality of fast fashion’s damage, and reveal the true price of trendiness.

Water usage

When thinking about garment production, a common misconception is that it only takes a mix of textiles and sewing methods to craft a t-shirt or pair of jeans. Unfortunately, what gets ignored is the mass consumption of water that occurs during the production process. Approximately 93 billion cubic metres of water are consumed every year in the garment industry, which would be enough to meet the needs of 5 million people.

90% of these garments are made with cotton or polyester, cotton being a major section of the water-guzzling garment train. Although polyester, which is a synthetic textile, takes oil to produce, cotton requires large amounts of water and pesticides to produce.

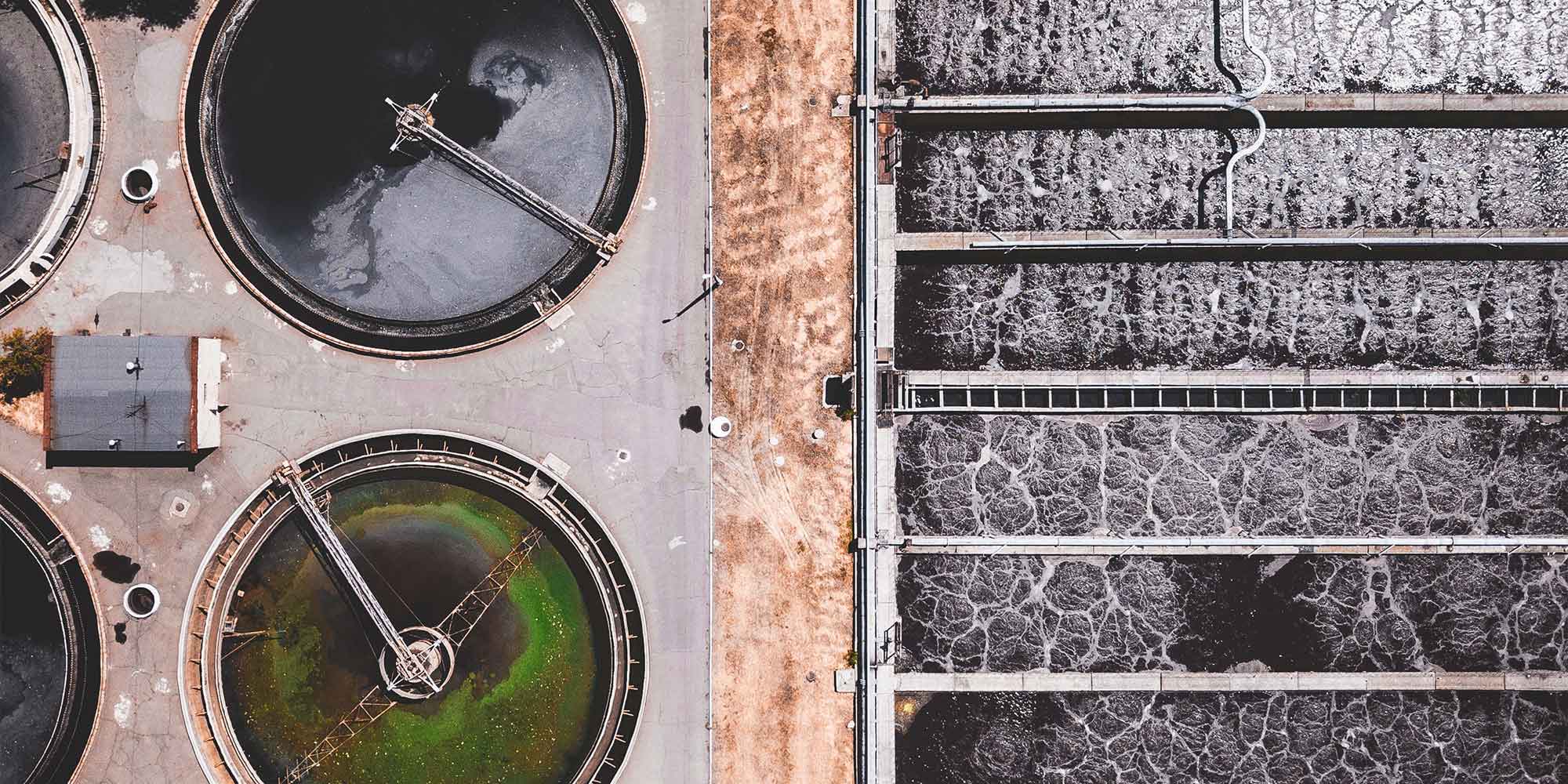

But fabric production isn’t the only thing impacting fast fashion’s water usage. About 20% of our world’s wastewater is a direct result of fabric dyeing and treatment, with this untreated wastewater being pumped back into our water systems, contaminating its contents with toxins and heavy metals. Not only does this negatively impact the health of the water itself, but also the health of the animals that consume it, including us as humans.

Textile waste

Ready for a terrifying statistic? Here it is: 92 million tonnes of textile waste is created each year, worldwide. By 2030, we are expected to discard more than 134 million tonnes of textiles per year. 95% of these textiles could be reused and recycled, but due to the model of fast fashion, this isn’t encouraged. The constant trends and guise of “affordability” causes us to believe that the clothing we buy is disposable. If you’re going to buy the latest fashions, you have to feel comfortable getting rid of the old ones. But while we’re purchasing new garbs, our tossed-aside garments are being sent into landfills.

In 2018, 17 million tonnes of textile waste ended up in landfills, which can take up to 200 years to decompose. To this day, 84% of clothing still ends up in landfills or incinerators. Even the second hand dealings of the fast fashion industry have caused unseen global pollution. In the United States alone, unsold clothing is exported overseas to be “graded” (sorted and resized) and sold in low/middle-income countries. Due to the fragility of some of these country’s municipal waste systems, whatever isn’t sold in these second hand markets becomes solid waste, creating health hazards through the clogging of rivers, greenways, and parks. The toxicity of textile waste is slowly choking our environment and poisoning our ecosystem, for nothing more than to dispose of garments fast fashion brands overproduce on the daily.

Carbon emissions

This might come as a shock, but the apparel industry is the penultimate industrial polluter, accounting for 10% of global carbon emissions. This is second only to oil, which still takes the lead as number one. Frankly, this is an embarrassing position to be in for the industry, and at this rate, their greenhouse gas emissions will increase by more than 50% by 2030.

Not only do these calculations account for emissions released during textile and garment production, but also the carbon that’s released during global transportation, and when textiles are stuffed into landfills. Let’s go back to the pair of jeans I was discussing earlier. The amount of water it takes to produce those jeans and place them in stores equates to the emission of about 33.4 kilograms of carbon equivalent.

In terms of the global fashion industry as a whole, with production and shipping, carbon emissions are virtually inescapable. But with the large quantities of clothing that are grown, manufactured, transported, and discarded in fast fashion, it renders the amount of emissions inexcusable. An estimated 1.2 billion tonnes of carbon is released due to the fast fashion industry alone! With those odds, the price of fashion is increased global warming.

Environmental injustice & poor working conditions

What you’ll notice when reading this article is the cyclical nature of environmental damage that occurs during the manufacturing of fast fashion. Overproduction leads to the overuse of water, resulting in wastewater. An excess of textiles leads to an excess of garment disposal, resulting in carbon emissions. A vicious cycle, but its effect isn’t just found on land and sea. A major portion of the industry’s environmental impact is in the quality of life of those who work in garment factories and live in areas affected by these textile and wastewater dumps.

The United States Environmental Protection Agency defines “environmental justice” as “the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, colour, national origin, or income, with respect to the development, implementation, end enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies.” Basically, it is the environmental equity of all racial and cultural groups, ensuring they have access to such things as clean water, safe homes, and healthy food. But for fast fashion brands, the only way to offer garments at a cheap price is through cheap labour, especially when clothing demands are increasing year by year.

Among the 80 billion pieces of new clothing that are made each year, most of them are assembled in places like low-income areas of China and Bangladesh. In fact, 90% of the world’s clothing is produced in low and middle-income countries as a means of cheap labour. This means the solid waste produced from textiles and the chemicals released by toxic dyes are being dumped in their ecosystems, jeopardizing their health.

Because of the oftentimes faulty political infrastructures of these low/middle-income areas, occupational hazards aren’t taken into consideration. Safety standards in workshops often go unenforced. Lung disease caused by cotton dust and synthetic air particulates. Overuse injuries caused by repetitive motions and lack of sufficient breaks. Deaths have also been reported due to these hazardous conditions, such as the 2013 Rana Plaza collapse in Dhaka District, Bangladesh. After discovering cracks in the foundation on April 23rd, the eight-story commercial building, known as Rana Plaza, had an immediate evacuation of all employees and businesses. But the building owners decided to neglect these warnings, and forced their garment workers to return. Rana Plaza collapsed the following day. 2,500 people were injured. 1,134 died.

Though this is one of the more extreme cases, it’s not an exception, as it shows the true extent of these occupational hazards and workplace neglect. One could say that a clothing brand can’t be held responsible for the choices made by building owners and factory managers. Even if this were the case, the fact that these fast fashion brands have continued to choose unregulated forms of manufacturing means they’re placing “affordability” over safety, supporting the hazards in workplaces and communities to maintain fast production.

What can change

Everything we have covered so far about fast fashion’s environmental impact might have come as a bit of a rude awakening, but don’t lose hope: some steps have been taken in order to pull back the industry’s footprint. Back in the summer of 2019, the global coalition The Fashion Pact was created, where luxury and fast fashion brands (including Adidas, Chanel, and H&M) developed a common agenda to begin more environmentally friendly ways of production. Unfortunately, this significant gesture has yet to be the saviour the industry needs. Only 32 of these brands joined this coalition, which is low in comparison to the 80+ brands out there. If all of these brands committed themselves to more eco-conscious means, the carbon footprint could be significantly reduced by 2030. Eco-conscious means include repurposing unused textiles, purifying water after the dyeing processes (or better yet, engaging in waterless dyeing), upholding safe and ethical workplace practices, and discontinuing the use of plastic packaging. But it isn’t just the fast fashion companies that need to change.

We as consumers not only need to rethink who we’re buying our clothing from, but how we’re handling that clothing. This includes repairing, donating, or reselling our old garments, instead of just throwing them in the trash, where they will inevitably wind up in a landfill. It means adopting handwashing practices where possible, as to avoid excess microfibres being dumped in our oceans from washing machines. We should also make sure all packaging is properly disposed of, through means of recycling and composting (depending on the materials).

If you want more information regarding environmental developments and mandates, check out the Fashion Pact’s 2020 Progress Report, where you can read about their brands, goals, and what they were able to achieve in 2020. The Global Fashion Agenda is also a top-notch resource when it comes to the latest in fashion eco-consciousness, releasing yearly reports. As always, Good On You has been committed to updating our ratings and content, for anyone who needs more guidance on which brands to embrace, and which ones to avoid. With more consumers being interested and invested in sustainable fashion, here’s hoping that enough pressure will be placed on the industry, and that fashion as a whole will begin to slow down.

Author bio: Delilah Smith is freelance journalist, storyteller, and sustainable fashion advocate from Oakland, CA. After changing her career path from editorial to film, she balances her position at Pixar Animation Studios with her Good On You contributions, returning back to editorial to spread awareness on the environmental effects of fast fashion, and give readers more eco-conscious choices. When not writing, you can find her on an aerial silk, which everyone should try at least once! You can find her on Instagram @delilah.the.dahlia